A fool you know, is a man who never tried an experiment in his life

Erasmus Darwin was one of the greatest polymaths of the 18th Century. It has been said that no one since has ever rivalled him for achievements in such a wide range of fields.

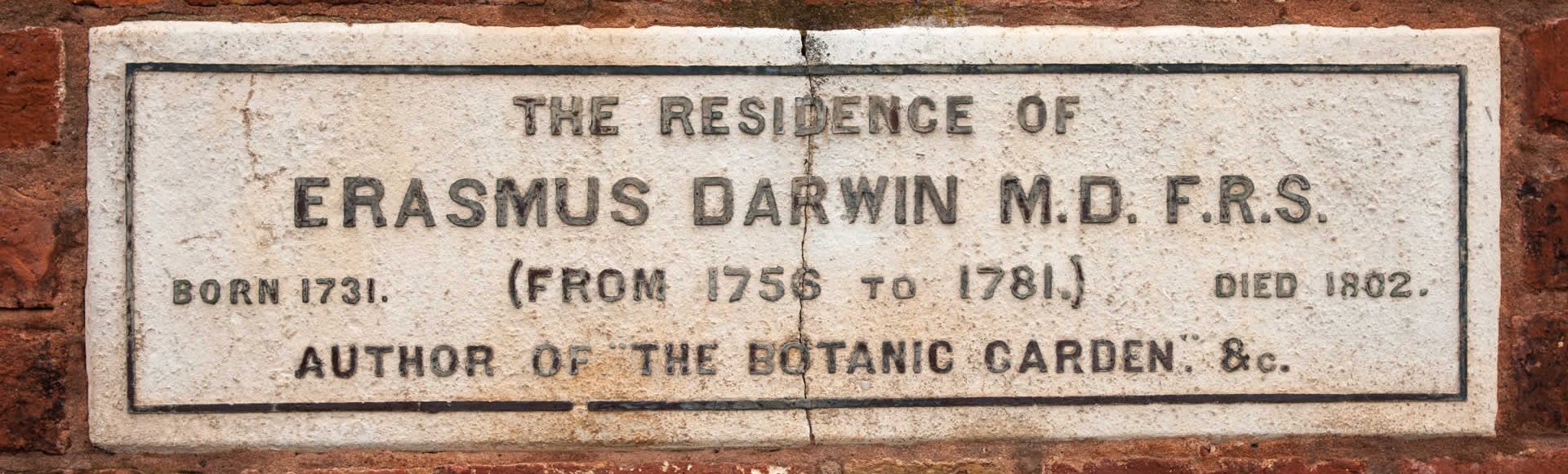

Born at Elston Hall, near Newark, Nottinghamshire, on 12th December 1731, Darwin was the youngest of four sons who became one of the foremost physicians of his time; indeed King George III asked him to be his personal physician but Erasmus declined, preferring to stay where he had settled in Lichfield, Staffordshire. He is responsible for the enlargement of the original house and its noble Palladian frontage on Beacon Street. With his ability to make friends Erasmus soon built up a vast network of associates, men and women like himself who independently became known as the leading social and philosophical lights of their time. With contacts like Matthew Boulton, Josiah Wedgwood, and James Watt he set up the Lunar Society which became the main intellectual powerhouse of the Industrial Revolution in England.

Born at Elston Hall, near Newark, Nottinghamshire, on 12th December 1731, Darwin was the youngest of four sons who became one of the foremost physicians of his time; indeed King George III asked him to be his personal physician but Erasmus declined, preferring to stay where he had settled in Lichfield, Staffordshire. He is responsible for the enlargement of the original house and its noble Palladian frontage on Beacon Street. With his ability to make friends Erasmus soon built up a vast network of associates, men and women like himself who independently became known as the leading social and philosophical lights of their time. With contacts like Matthew Boulton, Josiah Wedgwood, and James Watt he set up the Lunar Society which became the main intellectual powerhouse of the Industrial Revolution in England.

Among Darwin’s many talents was his extraordinary scientific insight in physics, chemistry, geology, meteorology and all aspects of biology. His theories of biological evolution by means of natural selection, although criticised by the church, were handed down from father to son and to grandson; but it was left to his grandson, Charles, to make case for biological evolution. Towards the end of his life Erasmus Darwin gained recognition as the leading English poet of his day.

If anyone would like to do further research on Erasmus Darwin, his place in history or as a man of science; or has anything to add to the investigations already undertaken on the Period of Enlightenment, then we would be interested to hear. For additional reading material please see the Book List on the website.

Erasmus Darwin; 1731 – 1802

Erasmus Darwin was Charles Darwin’s grandfather. A highly-regarded doctor – George III asked him to be his physician, but Erasmus declined – critically-acclaimed poet, ahead-of-his-time inventor and dedicated botanist, Erasmus brought tremendous enthusiasm and intelligence to all his multifarious pursuits. As a leading light of the Lunar Society his close friends and associates included Josiah Wedgwood, Matthew Boulton and James Watt, as well as the philosopher and statesman Benjamin Franklin and artist Joseph Wright.

Erasmus Darwin was Charles Darwin’s grandfather. A highly-regarded doctor – George III asked him to be his physician, but Erasmus declined – critically-acclaimed poet, ahead-of-his-time inventor and dedicated botanist, Erasmus brought tremendous enthusiasm and intelligence to all his multifarious pursuits. As a leading light of the Lunar Society his close friends and associates included Josiah Wedgwood, Matthew Boulton and James Watt, as well as the philosopher and statesman Benjamin Franklin and artist Joseph Wright.

Erasmus came up with a coherent theory of evolution a full 70 years before Charles turned his mind to it. He expounded this in his extraordinary book Zoonomia or the Laws of Organic Life which, first published in 1794, took him 25 years to write and also includes a comprehensive classification of diseases and treatments. Although the whole project appears somewhat eccentric to a twenty-first century reader, the book was, in its time, extremely well-received. One reviewer claimed that Zoonomia ‘bids fair to do for Medicine what Sir Isaac Newton’s Principia has done for Natural Philosophy.’ It didn’t, but it was a nice thought.

Erasmus’s belief in evolution initially flowered while he was in his thirties. His first public statement of his theory was somewhat unusual and designed, as his biographer Desmond King-Hele explains, to publicise his theory ‘without anyone noticing’:

‘His family coat of arms consisted of three scallop shells. What a good idea to add the motto E conchis omnia, or ‘everything from shells’. It was not exactly right … but it expressed the essence of evolutionary development.

In 1770, Erasmus had this motto painted on his carriage, in 1771 he added it to his bookplates. Unfortunately, the Canon of Lichfield Cathedral, the Revd Thomas Seward (father of the poet Anna), spotted the reference, and – in satirical verse – accused his neighbour and physician of renouncing his creator, and exhorted him to change his ‘foolish motto’ or risk the defection of some of his patients. Erasmus painted over the motto on his carriage. It was, says King-Hele ‘a humiliating climb-down.’

In person Erasmus was friendly, generous, sociable, full of teasing humour, and, according to his friend James Keir, ‘paid little regard to authority’. He was married twice – both times to women he adored – had an in-between mistress, fourteen children and dozens of lifelong friends. Erasmus also enjoyed his food. He enjoyed it so much that as he grew older, a semi-circle had to be cut out of his dining-table to accommodate his considerable bulk. An obsessive inventor of mechanical devices, he developed a speaking machine, a copying machine and the steering technique used in modern cars. Erasmus was the first person to fully understand and explain the process of photosynthesis in plants and to describe the formation of clouds. He translated Linnaeus’s influential Systema Vegetabilium – the system of plant classification that forms the basis of modern botany – from Latin to English, wrote a treatise on the education of girls, and was passionate about the abolition of slavery.

Erasmus Darwin died on Sunday 18th April 1802, probably of a lung infection. His final volume of poetry – The Temple of Nature or The Origin of Society – was published posthumously. To find out more about him, his life and work, read Desmond King-Hele’s biography Erasmus Darwin: a Life of Unequalled Achievement or Jenny Uglow’s The Lunar Men.

The Lunar Society

The Lunar Society of the 18th century were a proud society of individuals in the West Midlands Region. An impressive Alumni includes some of the world’s most inspiring and intriguing characters, such as Darwin, Wedgwood, Boulton and Watt.

For extracts from some of Erasmus Darwin’s poems click here.

Recent Unpublished Writings about Darwin

Click on the papers to read – all by Canon A Barnard, Executive Committee member at Erasmus Darwin House

- Truth, Faith and Doubt in some C.18th and C. 19th Scientists – coming to terms with faith and the biblical record

- Staffordshire’s Involvement with Genesis and Evolution – Erasmus Darwin, Floyer, Whitehurst and Bateman

- On the Shoulders of Giants – the evolutionary story from Erasmus Darwin to Charles Darwin